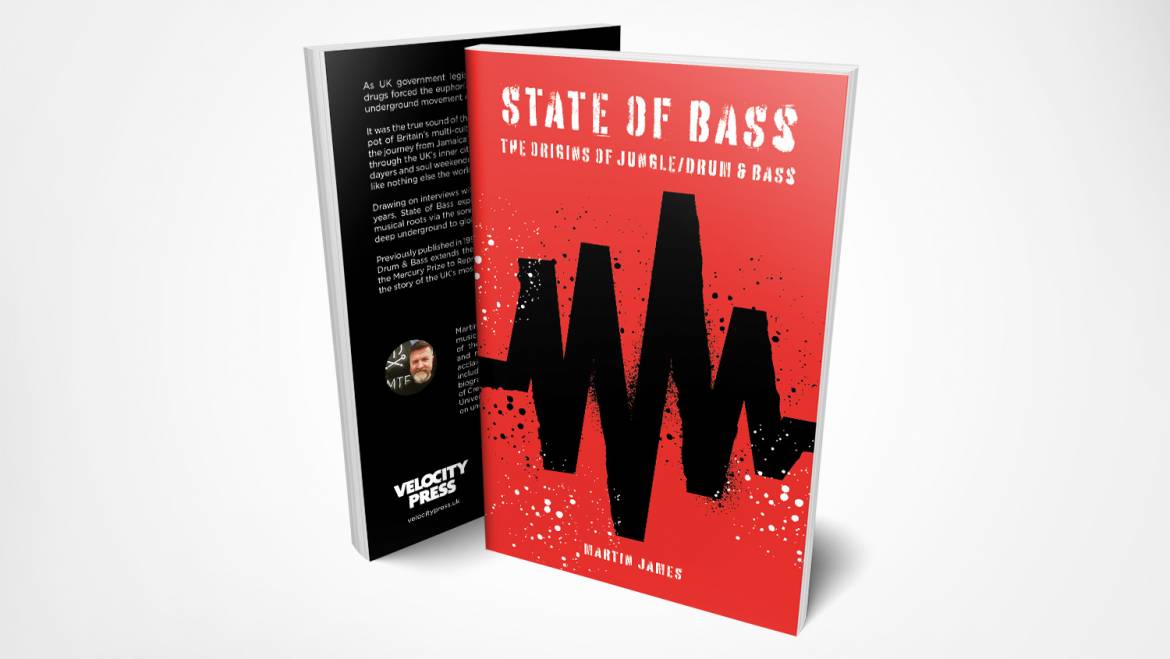

Veteran music journalist Martin James (Melody Maker, Muzik, DJ, Mixmag, Electronic Sound) wrote the first book on jungle/drum & bass back in 1997. Entitled State of Bass: Jungle – The Story So Far, it had sold out by 1998 and has never been reprinted. Until now. We’re publishing a revised reissue entitled State of Bass: The Origins of Jungle/Drum & Bass in March 2020. The updated version extends the original text to include the award of the Mercury Prize to Reprazent and previously unpublished interviews with Roni Size, Goldie, LTJ Bukem, Fabio, Shy FX and other key players from the early years of the scene. In this exclusive excerpt from the Knowledge Magazine 25th Anniversary book, Martin James reflects on the cultural roots of jungle/drum & bass and its relationship with the mainstream media in the 90s.

When Roni Size & Reprazent beat competition from The Prodigy and Radiohead to win the Mercury Prize for the 1997 album New Forms it seemed like mainstream culture fell over itself to try and understand both the album and the scene it came from.

Milled in the ferment of the uniquely British underground phenomenon of jungle and drum & bass, New Forms sounded simultaneously classic and future bound. It drew its hooks from the multicultural hues of urban Britain and linked them through the historical lines of reggae, dub, jazz, soul, funk, rare groove, acid house, bleep and hardcore.

It was a sound woven along the threads of the misunderstood fault lines of post-Windrush Britain where the progeny of the earliest arrivals soaked up British cultural influences and in return provided a deep influence to UK popular culture. The cultural roots of soundsystems, blues parties and shabeens spread to newfound friends and changed our music, our art… our lives forever. New Forms then was an expression of the post-Windrush British experience of a range of popular culture expressions, from Jamaican heritage sounds to daytime TV; US soul and jazz to UK rave.

New Forms was also the sound of the impact of that Windrush experience on white British youth. It comes as no surprise that the album was birthed in Bristol, a city steeped in not only the history of slavery but also one of the UK’s first cities of music cultural fusion. Bristol’s St Paul’s was famed for its soundsystems and blues parties, just as the broader area of the Avon was notorious for the free parties of the traveller movement and, later, the renegade countryside takeovers of the urban ravers.

Roni Size and his collaborators may have been extending the rich lineage of black British music, but they were simultaneously an extension of Bristol’s multicultural punk, post-punk, hip hop and club scenes that produced genre contortionists such the Pop Group, Rip Rig and Panic, Neneh Cherry, Massive Attack and Tricky. Journalists and critics who later tried to differentiate jungle and drum & bass along the racial lines of blackness and whiteness missed the point by an inner city mile.

What New Forms represented then was the true sound of British urban youth at the end of the twentieth century. Coverage in underground dance music magazines was a given. The album also captured the imaginations of the glossy dance press, the rock and indie-heavy weekly music newspapers, the style magazines, the serious daily newspapers and the wider mainstream media. This wasn’t a surprise. Many journalists from these publications and media outlets had been all over jungle and drum & bass from the start.

It’s worth noting that the first serious mainstream article on jungle in the national press was in The Times newspaper and not the music press. Reviews of jungle raves and drum & bass clubs would become regular fare in newspapers like The Guardian, The Independent and even the right-leaning Daily Express. Far from being ahead of the pack, the national dance press emerged alongside NME and Melody Maker who too were quickly onto the scene.

Mainstream radio had also been unusually quick to pick up on the buzz. Responding to the wall-to-wall pirate pressure and Kiss FM’s early support, Radio 1 even hosted a short series of special shows called One in the Jungle in 1995. These newspaper features, magazine articles and radio shows were driven by journalists, critics and producers who were former, or active ravers. They understood the significance of the music and its subculture. They were the friends within.

Hours after the Mercury was awarded I found myself being chauffeured across London to a series of the capital’s new rooms. Sky News wanted to know what on earth drum & bass was. BBC News 24 asked about Bristol and managed to link their questions to the St Paul’s riots of 1980. The ITV news wanted to know if giving the Mercury Award to an album from the drum & bass scene was in some way supporting the drug culture associated with raves.

Channel 4 were more interested in finding out about the cultural significance of the jungle and drum & bass scenes. When I said it was the most important British phenomenon since punk rock in 1976/77 Channel 4 News seemed delighted. I’d given them a hook their viewers would recognise. For the record, I’d also described New Forms as ‘this generation’s Sgt Peppers Lonely Hearts Club Band’ in weekly music paper Melody Maker. I don’t think either was entirely accurate, but the aim was to show older music fans of The Beatles and punk that Roni Size’s album had a huge cultural significance that couldn’t be ignored.

One thing unified all of these news channels though – a look of disappointment when a home-counties raised white guy in his mid-thirties walked onto the set and not the young kid of blended parentage from one of London’s urban ghettos that they’d hoped for. I’d been invited into these newsrooms because earlier that year I’d published State of Bass: Jungle – The Story So Far, the first serious book-length investigation into the jungle and drum & bass nexus.

Sadly, who I was didn’t support stereotypical ideas of authentic breakbeat science or scientists. Not that I ever claimed to be a part of the scene. Indeed, in the introduction to the original book, I admitted that I was never a junglist, rather I was someone drawn to the music and the scene by its unadulterated power.

This admission alone was enough for at least one UK national music magazine to slate both me and the book in an unprecedented full-page review. I wasn’t authentic enough to be writing about this music! I was too white, too middle class, too suburban – the antithesis of the jungle/drum & bass movement that was being defined by the media along the lines of race, class and location.

This idea that journalists writing about so-called urban scenes like jungle/drum & bass were expected to be ‘from the scene’ in order to retain an authentic voice was out of step with an egalitarian post-rave culture that celebrated the experience over the star. Magazines like NME, Q, Mojo etc. remained obsessed with long rejected ideas about subculture and authenticity.

They clung to the approaches of ‘golden age’ journalists who celebrated stars. They produced lists of essential albums made by people who were mainly representations of themselves – middle-class white men. They pretended to be free from commercial constraints, untouched by the industry, yet they colluded with the industry to create cover stars in order to increase advertising revenue and sell more copies of their magazines in a deal with the music industries that ignored the fact that they were complicit in the process of selling product to consumers. My face simply wouldn’t do that for them.

No one from the scene ever said this to me though. Most people were extremely supportive and got the fact that I loved the music and didn’t claim to be from the scene. They appreciated my honesty. Although the following year, Goldie would adopt that reviewer’s confrontational stance when I asked him a question about the scene during an interview in support of his 1998 album Saturnz Return. Goldie took offence, jabbed me in the stomach and said he was ‘sick of middle class white guys telling me how things were in the scene’. ‘Where were you back in the day?’ he demanded. My reply was simple, I was there on the frontline observing, writing and capturing the moment. It wasn’t my moment to claim, but it was important to document. He was complimentary about my Stussy bench coat though!

To be a junglist was to live and breathe the scene, the sounds and the style. It was all about being there, a face in the crowd at the clubs and raves, nodding with approval as the DJ dropped the latest upfront dubplate or cued up a tune straight from the studio on DAT. It was all about the subconscious sharing of those collective threads of knowledge and experience that tied people into the greater fabric of culture and community. It was about family and a sense of belonging. A junglist diaspora.

As I’ve already said, I could hardly have called myself a junglist, but I loved the music, the style, the raves. I had done since I first stumbled upon ‘Eye Memory’ by Nebula II on Reinforced Records at a rave in Nottingham’s Marcus Garvey Centre. A dark and brooding slice of post-hardcore psychosis, its breaks seemed to snap at the synapses, sending my already fried brain cells reeling in unadulterated frenzy.

Nebula II was a local crew who had honed their craft in the city where house music was first played by Graeme Park at a funk all-dayer in the unlikely surroundings of the Rock City nightclub. House quickly became a staple of his sets at The Garage club before he shared his tunes with the Hacienda in Manchester.

Nottingham’s central role in the creation of a UK house scene has almost been written out of history in favour of Manchester and London. Back then though Nottingham, the Queen of the Midlands, was rave central. Little surprise then that the darkcore sounds of Nebula II were at the forefront of a UK post-hardcore breaks explosion that was just on the horizon.

The progression through dark, jungle tekno and drum & bass was as exciting a time in British club culture as had ever been witnessed. In recent years we’d raved while the rest of the world went through epoch-defining political change. Communism had collapsed across Europe, the Berlin Wall was dismantled, a lone figure held up a fleet of tanks in a student uprising in China’s Tiananmen Square. In the USA President George H. W. Bush reneged on election promises and increased taxes to fund a war in the Gulf of Iran. The UK had just lived through ten years of Thatcherism, which brought destruction of the unions, poll tax riots and a rise in the underclass via poverty on a huge scale. The world seemed to be in a state of disarray, history was collapsing.

The jungle/drum & bass nexus was the sound of that collapse. It captured the emergence of accelerated culture as we started the race towards the end of the millennium. It was a sound that fed on music history and spat out high speed, cut and paste montages of sound. It was a collision of the be-bop of the jazz pioneers, the deepest dub cuts of the soundsystems, the crystal clarity of Kraftwerk’s electronica, hooks from the electropop of Gary Numan and Japan, electro’s body-popping twists, house music’s soul, techno’s pulse, the breaks and beats of funk, hip hop’s ingenuity and the electro-acoustic mood boards of the film scores that had shaped the imaginations of the generation.

The scene, the sounds, the style were a mash-up of cultures all responding to the anger, the joy and the high-speed chaos of the times. It was also a scene driven by cheap technology. This was the period that saw the emergence of the games console as a core element in youth culture, the home computer wasn’t unusual, the mobile phone was increasingly commonplace, and sampling equipment and sequencing software become cheap enough for a wide range of people to get hold of. No longer was it just for the wealthy.

State of Bass: The Origins of Jungle/Drum & Bass is a reworking of the original text to include further insight into the cultural significance of that period. Historically it extends to the phase when Roni Size won that Mercury and Goldie’s second album Saturnz Return. This is in part because I’ve always felt that the original book came too soon. It charted the rise before any mass cultural peak had been witnessed. The Mercury Prize was that moment.

Saturnz Return, on the other hand, represents the period when the mainstream cultural industries lost interest in their investment. Jungle and drum & bass simply didn’t translate to huge income for them and as the sound of poor reviews for Goldie’s second album resounded everywhere so too did the cacophony of mainstream industries running towards ‘the next big thing’.

In the wake of the mainstream’s retreat jungle/drum & bass was restored as an underground phenomenon where it has existed as an ever more powerful presence ever since. The Prodigy’s Liam Howlett once described it as ‘the UK’s only true underground’. He was right. Its significance is immeasurable. State of Bass: The Origins of Jungle/Drum & Bass aims to make sense of this impact of Britain’s urban underground by taking a fresh look at the period of the 90s that music journalists now often tell us was all about Britpop.

So often forgotten in the rewritten histories of the 1990s, jungle/drum & bass lit the furnace of the urban British youth culture that surrounds us today. Put simply, it was the real cool Britannia.