In our new monthly, we’ll shine a light on some of our favourite podcasts. We’ll be talking to their creators about what goes into their podcasts’ making, and why you need to listen to them.

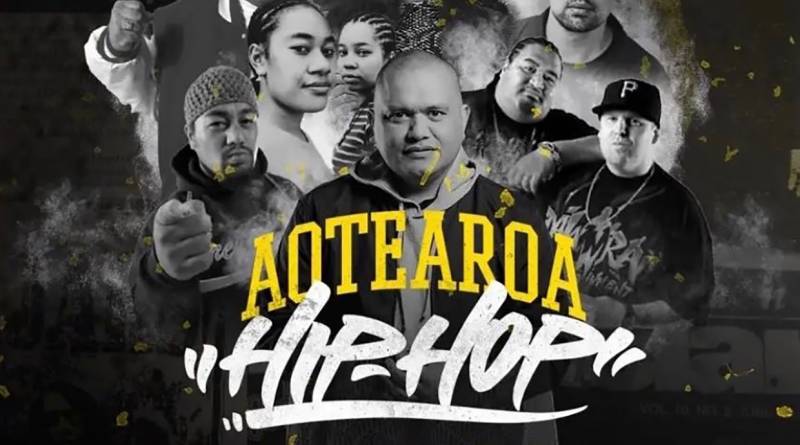

For our first podcast spotlight of 2022, we chatted to music journalist Martyn Pepperell about The Aotearoa Hip-Hop Podcast. The podcast is a comprehensive history of the often-overlooked hip hop scene in Aotearoa (the Māori name for New Zealand). Every episode combines interviews with Aotearoa’s hip-hop pioneers and some of their classic records to paint an in-depth picture of a scene many people have never heard of.

The first season, episodes one to six, focuses specifically on the scenes development from the early 80s through to the early 90s. If you’re looking for an excellently soundtracked, precise and detailed history of the stories and people of a truly underground scene, look no further than The Aotearoa Hip-Hop Podcast.

How did you get involved with the Aoetearoa Hip-Hop team? Was there a reason the team chose to tell the story of hip-hop in Aoetearoa orally, as a podcast?

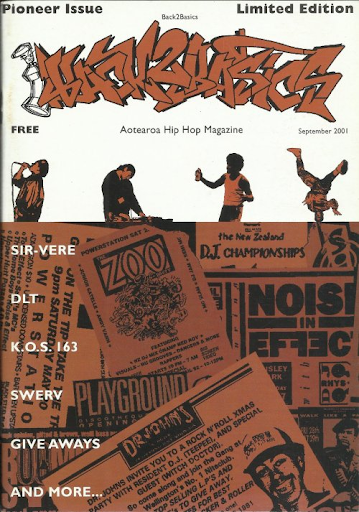

There was one reason I worked as a researcher, writer and producer on this podcast: Phil Bell aka DJ Sir-Vere asked me to get on board. Phil and I had previously worked together in the late 2000s and early 2010s, when he was working as the editor of the quintessential, now shuttered, Aotearoa hip-hop magazine, Back2Basics.

In the years after Back2Basics, Phil and I stayed connected on social media and used to run into each other at concerts and festivals around the country. When he hit me with the vision, making a documentary-style podcast about the history of hip-hop in Aotearoa New Zealand, yes was my only possible answer. Phil’s been a huge figure in the local scene for decades and along the way, he’s worked with everybody, sometimes literally dragging people over the finish line with him. I knew the scene would respond well to a project fronted by him, and that was that.

In terms of what you’re asking, however, I didn’t really think about the format at the time. I just zoned in on putting the story together with Phil. However, since the release of season one, I’ve realised how powerful using an oral storytelling form has been, and how smart of a choice it was. I’ve been writing about music, both at home and abroad for close to fifteen years, and this project has, time and time again connected me with people who have never read anything I’ve written, which has been very exciting and humbling.

Do you think the fact Aotearoa is an island had any impact on such an intricate, tight-knit Hip-Hop community being built on it?

It’s a small place, as most islands are. The cities are small, and when you’re in the music scene, everyone tends to eventually meet everyone, in one way or another. That was true then and it’s still true now. Pre-internet, you had to get creative to be ahead with music. In Wellington – the city I grew up in – the scene was lucky that an American basketball player who moved here, Kenny McFadden, was able to get his older brother to mail him cassette tapes of New York hip-hop radio on a fortnightly basis. That really pushed things along.

We were also lucky that Dean Hapeta aka D-Word from Upper Hutt Posse, the first hip-hop group in Aotearoa to release a single, ‘E Tu’, had the prescience to find the NME, scour it for mail order shops and send money orders off to the UK to get highly sought after hip-hop, reggae and dub 7”s, 12”s and LPs mailed to him. Dean was ahead of the record buyers, and when he came into town with a boombox and cassette tape recordings of songs like ‘Planet Rock’ and ‘Go Deh Yaka (Go To The Top)’ by Monyaka, ears pricked up.

The podcast mentions travelling to the US to get in contact with DJ Tee Pee. How hard was it tracking down Aotearoa’s hip-hop pioneers?

With Tee Pee, it was really simple. We knew we’d get a better interview with him in person and we had the funding to get it. This was before the pandemic set in and it was a no-brainer. A lot of the known names were very easy to track down. What was harder was finding the forgotten characters. Truthfully, even though we conducted over one hundred interviews, we didn’t actually manage to get everyone we wanted. Sometimes we couldn’t find people, other times they didn’t want to revisit their past. It is what it is. You have to move respectfully and understand that not everything is meant to be.

The Podcast is well soundtracked with the fundamental Aotearoa Hip-Hop tracks as well as classic US records that influenced the scene. Was it difficult assembling these records? Was there lots of digging for rare pressings of vinyl records, or were some available digitally?

The US side of this was very easy. DJ Sir-vere has been DJing since the late eighties, so he was able to pull out the right records for the eras with an almost automatic recall. If you asked him, he’d tell you it was hard, but the ease with which he did it was a testament to why he’s been able to spend a lifetime working as a club, radio and mixtape DJ.

The Aotearoa side was harder. We were bidding on rare records online, digitizing cassette tapes, begging archivists and scene heads to lend us copies to digitize. At the same time, most of the really classic or obvious local music was easily available online. As a byproduct of this, I recorded a couple of Aotearoa hip-hop DJ mixes for NTS and Dublab

Are there any playlists/mixes out there you would recommend someone listen to if they are keen to learn more about the history of Hip-Hop in Aotearoa and its sonic origins?

As per the last question, I’d recommend you check out the series of Aotearoa hip-hop, street soul and swingbeat mixes I recorded for NTS and Dublab over the last two years: ‘Closer’, ‘Seasons’, ‘Peoples’ and ‘Summer in The Winter’.

If you want to go further, DJ Sir-Vere recorded a very respected and well-selling series of hip-hop mix CDs in the 2000s and 2010s called ‘Major Flavours’. Some of those have locally focused bonus CDs. If you can find them, they’re like gold. Another slab of gold is ‘Aotearoa Hip-Hop Vol.1‘, a compilation album Mark James Williams aka Slave aka Loggy Loggy assembled for a major label in the late 90s. It’s loaded with quality local classics.

In episode two, parallels are drawn between the Sex Pistols’ infamous 1976 gig at Manchester’s city hall, and one of Aotearoa’s most infamous hip hop events: RUN DMC at the Power Station. How much influence did the UK have on Aotearoa hip-hop, or was the scene pretty independent from it?

One thing about music in Aotearoa is due to our historical colonial links to the UK and the global cultural dominance of the US in the 20th century and early 21st century, we got influenced by both sides of the Atlantic. That Run DMC gig you mentioned, London’s very own Derek B – Rest In Peace! – was one of the support acts, and in an understated way, his stage show was just as much of an influence on the first generation of Aotearoa rappers as Run DMC was.

I doubt you’ll find this surprising, but Soul II Soul and M|A|R|R|S were huge here as well. We go into more detail about the influence of Soul II Soul on music in Aotearoa in episode five of season one. Retrospectively speaking, it’s pretty clear that Aotearoa had something close to its own Street Soul and New Jack Swing scenes. I’ve recorded a couple of mixes for NTS and Dublab diving into these topics in the past.

The UK influence continues to this very day. Just the other week, I saw some kids filming a music video for a drill style song down on the waterfront. They were doing it in their own way, but the UK touches were very much there.

Episode two also mentions Greg Churchill, a successful house DJ from Aotearoa. Did rap dominate over dance music in Aotearoa, or were there any overlaps between rave and hip hop culture?

Okay, so as in many scenes around the world, a lot of 90s/2000s Aotearoa dance music DJs, whether they were working in house, techno or jungle/drum and bass, got their start as hip-hop DJs in the late 80s and early 90s. Greg was part of that generation.

By the early 90s, DJs were mixing hip-hop and house together at warehouse parties and nightclubs across the country, and sharing the stage with live hip-hop acts, and sometimes rock acts. Rave very much happened here. Outdoor parties very much happened here. The legacy of all of that endures here in a multitude of different ways. These days it’s more stratified into commercial festivals and underground club gigs, but the spirit of the rave era continues to sit as part of the context of dance music in Aotearoa.

Over the decades, hip-hop and dance music continued to crossover. Sometimes hip-hop MCs would record songs with house or jungle/drum and bass producers, even joining them on stage. There have been plenty of remixes, and at one point there was a series of hip-hop vs drum and bass DJ battle nights. Hip-hop and jungle/drum and bass don’t always see eye-to-eye, but when they do, it’s beautiful. It’s worth noting that golden era Aotearoa hip-hop artists DLT, King Kapisi and Che Fu all included original jungle tracks or remixes on their albums and singles in the late 90s.

From filmmaker Taika Waititi to actor Rachel House, creatives from Aotearoa with Māori Heritage are becoming more well-known internationally. Do you think Māori people are gradually getting more global representation in the arts globally or is there far more work to be done?

I’d never claim to be able to speak for the Māori people of Aotearoa. However, individuals you’ve cited like Taika and Rachel, have had a powerful cultural impact outside of Aotearoa, and a long line of talent is walking in their footsteps or currently in the process of making their own mark out there in the world. It’s happened before, and it is inevitable that it will happen again. Shout out Te Whiti Warbrick aka Sickdrumz, who has contributed programming and production to hit singles by Rihanna and Future.

Also, I just want to spotlight Jess Hansell, the rapper, musician, writer, thinker and everythinger who’s made some brilliant music as Coco Solid and created a remarkable animated television show, Aroha Bridge. All I’m saying is, you need to see it. She also has a book coming out next year, How to Loiter In a Turf War. You’ll need to read it. Jess is one of many Māori names I could name within music, writing, arts and culture. Here are a few more: Mokotron, Noa Records, author Rebecca K Reilly and poet/writer Tayi Tibble.

There were several well-publicised incidents of gang violence in Aotearoa in the press across 2020 and 2021. Do you think Hip-Hop can help listeners better understand the causes of gang violence? Any up-and-coming Aotearoa rappers who are already doing this?

There is a long tradition in Aotearoa hip-hop of what I call reality rap, which often speaks to the realities of street life in Aotearoa’s more neglected suburbs. Some key figures in this include Ermehn, Over Dose, Sid Diamond and Mr Sicc. I say that to say this, numerous artists have recorded songs that provide commentary and context on gangs and gang life in Aotearoa, and have often been treated with bad faith by several generations of middle to upper-class New Zealanders who probably enjoyed rapping along to N.W.A, Snoop Dogg or 50 Cent when they were drunk on the weekend, before going back to passing judgment on people whose lives they don’t understand on Monday morning.

Ermehn speaks to all of this in the second season of the podcast, but in terms of contemporary artists, plenty of the younger rappers I mentioned earlier have songs that could help someone understand how and why gangs exist within society down here. The question really is, are you willing to actually listen to what they’re saying and think about it?

Were there any books, articles or written material that helped inform the podcast and/or your outlook on the Aotearoa Hip Hop scene?

It’s impossible to not mention and pay some respect to Gareth Shute’s book Hiphop Music in Aotearoa (2004), which is one of the original tomes on the stories of the scene.

I also need to mention another essential piece in the puzzle, Back2Basics magazine, which, as I mentioned earlier, was the quintessential Aotearoa Hip-Hop title. Back2Basics went through a few iterations over its lifetime. Respect to Sen Thong, Omega B, Ayesha Kee and the original crew. Also, shout out to Phil, Sarah Illingworth, Duncan Croft, Sam Wicks, Jaz Ford, Mark Thomson, Leilani Momoisea, Askew, Raymond Sagapolutele, and everyone else who worked on the second iteration when I was writing there.

Apart from that, I also want to mention a few key journalists who have written about hip-hop in Aotearoa over the years. Kerry Buchannan: who to paraphrase Stinky Jim, was the man behind a rap column that would sometimes mention Nietzche and Nelly in the same paragraph. Lisa Van Der Aarde: one of the first people who wrote about hip-hop in Aotearoa. Beyond that, the list continues: Nick Bollinger, Oscar Kightley, Murray Cammick, Graham Reid, and April K. Henderson.

The reality is that this podcast was informed by every interview we conducted, every conversation we had about it, and two years of watching youtube videos and reading article clippings from the late seventies until now. We couldn’t have done it without the work that several generations had already put in to begin and continue archiving the history of hip-hop in Aotearoa. If you don’t want a story to be forgotten, you have to keep retelling it using the mediums of the day – this is our contribution to the act of keeping it going.

The second season of Aotearoa Hip Hop Podcast is coming out in 2022, any hints as to what listeners can expect?

I’ll say only this. Season two begins in 1996 and ends in the mid-2010s. Over the course of six more episodes, we track the rise of the golden age of hip-hop in Aotearoa, artists like Che Fu, King Kapisi, Dam Native, etc, while setting the table for the emergence of the early 2000s generation of artists – Scribe, Dawn Raid Entertainment, Dei Hamo, David Dallas, Ladi6, etc.

If the late 90s set proved we could make hip-hop with a distinctive local voice, the early 2000s set showed the youth of this country that Aotearoa hip-hop could break sales records, dominate mainstream radio, and sell-out shows across New Zealand, Australia and sometimes beyond. It’s an inspiring story with touches of heartbreak and tragedy.

You can listen to Aotearoa Hip Hop on the Mai FM website, as well as on Spotify and Apple Music.

If you want to read more about hip-hop from around the globe, Laurent Fintoni’s Bedroom Beats & B-sides, explores instrumental hip-hop culture across Europe, America and Japan.