Our fourth book Bedroom Beats & B-sides details the rise of a new generation of bedroom producers in the instrumental hip-hop and electronic music scenes. Here author Laurent Fintoni explains how the idea for the book can be traced way back to 2008.

I’d like to tell you that there’s a clean and clear narrative to how this book came to be, but there isn’t. It has a few starting points. One of them is in a Berlin bar on a January night in 2012 when a stranger I’d just met told me I should write a book. I was in town to give a talk. That talk was based on a series of articles, written while I was living in Japan in 2008, and a mix, inspired by the articles and which I put together with some friends after my return to Europe in 2009.

Taken together, the articles, the mix, and the talk argued for a sonic lineage from boom-bap, the popular 1990s New York City hip-hop sound rooted in productions from the likes of DJ Premier and Pete Rock, to a then recent rise in instrumental hip-hop with an electronic slant, a new wave of beats that felt fun and exciting and built on more than a decade’s worth of experiments at the edges of hip-hop and electronic music. Upon hearing all this, the stranger casually dropped his recommendation. I was puzzled by the idea at first but eventually, it took hold and now, eight years later, the book is a thing. Let’s backtrack a little more though.

First and foremost, this book is the result of a personal journey through the beats of hip-hop and electronic music. My journey started in the early 1990s in the south of France when I was a teenager buying French hip-hop mixtapes and import CDs of American hip-hop acts. It continued when I moved to England in 1998 where I discovered electronic dance music and more mixtapes, albums, and odd instrumental music that didn’t quite fit the dominant narratives of house, techno, or rap music. Eventually, this fandom turned into research and writing about beats because while I always liked vocal music the beats were really what I had always connected with. Guru said it was mostly the voice, but what I really felt was Premier’s chops.

Fifteen or so years after I’d first discovered hip-hop and beats, I landed on this idea of connecting the boom-bap sound from the 1990s to the beat movement of the late 2000s via various strains of hip-hop and electronic music production that had happened in between. I wrote about it, discussed it with people in various countries, articulated it as a mix. And then someone told me I should write a book and the more I thought about it, the more I worked on it, interviewing artists and talking with them, the more it became clear that the original idea had to evolve.

The more I tried to pin down a narrative on boom-bap and its legacy, the more I realized it was about much more than just that. It was about technology. It was about the distinctions we make between hip-hop and electronic music. It was about two decades of giving weird names to beats and instrumental music because they didn’t fit the accepted narratives. It was about B-sides. It was about bedroom producers and their own journey from the sidelines to the stage. It was about a culture.

Over the past eight years I have written and uttered what feels like hundreds of variations of a sentence that begins with, “This book is about…”. At first, it was an exercise to try and clarify what I actually wanted to do. Then it became a way to try and explain the book to people. Eventually, it was the elevator pitch for a potential publisher. And yet that fragment of a sentence still feels frustratingly limiting. But you need to know what this book is about and I need to get on with telling you the story.

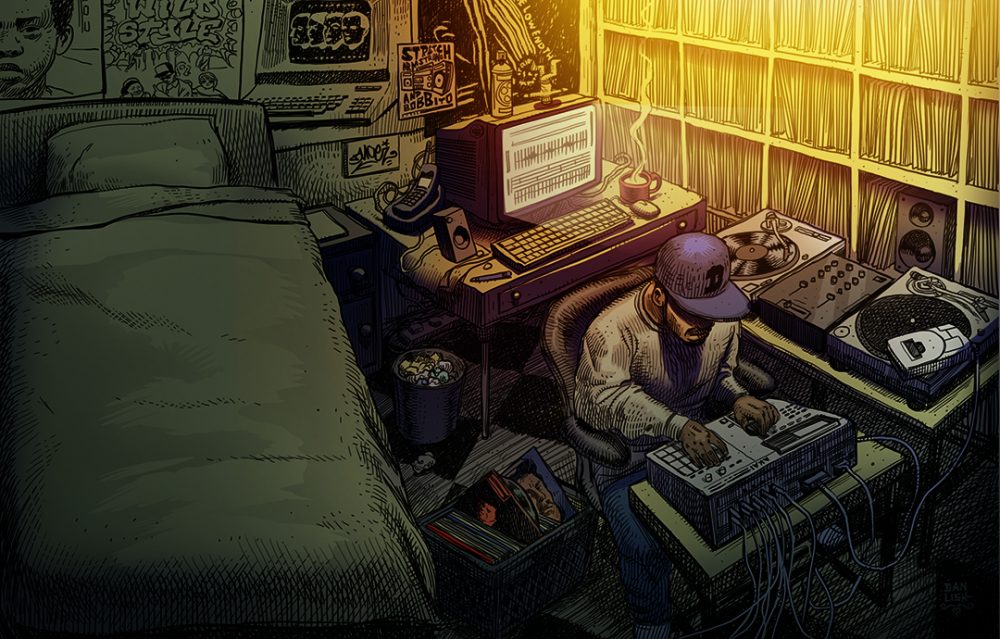

The first decades of the 21st century saw huge changes in the music industry as new technology transformed creation, communication and consumption. In all this turmoil one change occurred relatively quietly, almost naturally: so-called bedroom producers, music makers raised on hip-hop and electronic music, went from anonymous, often unseen creators to live performers and chart-toppers. Today, bedroom beats and the people behind them can be found in the Billboard charts, on music festival line-ups and in various popular playlists on Spotify, Apple Music, and YouTube.

Beyond technological and market forces, this change was foremost a cultural one, the latest manifestation of what we’ll call beat culture, a timeless, rhythmic continuum that stretches back millennia to the spiritual drums of African traditions. Driven by the democratization of music-making tools and bedrooms becoming studios, new musical movements emerged. Focused on experimentation, artists grasped the close relationship and potentials between hip-hop and electronic music in new ways.

Beginning in the 1990s with instrumental music for global hip-hop heads and rave comedowns and culminating at the end of the 2000s with young people playing beats from their laptops, these movements – known by a variety of names including trip-hop, downtempo, jungle, IDM, turntablism, leftfield/alt hip-hop, or just beats – acted as incubators for new ideas about music production and performance that are now taken for granted.

Invented by the music industry with the vinyl single in the 1950s, the concept of A- and B-sides was a commercial imperative to sell more records. It wasn’t long before artists and labels began to use the B-sides of singles to release material with less commercial appeal but more artistic potential. Some of those B-sides became unintentional hits, while others lingered in homes and record shops waiting to be discovered by curious listeners searching for more. Vinyl singles started being phased out in the 1990s as the industry shifted its focus to the massive profits heralded by CDs, yet sides remained an enduring reality in the DJ-led, burgeoning new markets of hip-hop and dance music.

More importantly, sides now existed as a concept in the collective imagination. For major labels, the word B-side was repurposed to mean any bonus material they could make money from, even if it was sold to you on a CD or digitally. For the more curious and adventurous consumers the B-side, whether literal or physical, represented a foundation of sorts on which the A-side rested. The A-side was the track everyone knew and loved, but the B-side was where you went to find the real gems. It was where indulgence and expression could take full flight via edits, instrumentals, versions, remixes, or even just sonic doodles. The B-side completed the artistic whole and opened up new worlds of possibilities.

Like a good B-side, the musical movements discussed in this book offered an alternative take often in close relationship to what was happening in the mainstream of hip-hop and electronic music. They filled in the gaps and sometimes found success, leaving a mark on our collective consciousness and expanding acceptance for what the music and its makers could be.

This book follows the B-side stories of hip-hop and electronic music from the 1990s to the 2010s, exploring the evolution of a modern beat culture from local scenes to global community via the people who made it happen – diverse groups of idealists on the fringes – and the social, technological, and cultural forces that shaped their efforts.

In the process of exploring this we will also grapple with the evolution of the music producer, the meaning of which has been stretched wide to accommodate different ideas of music creation and performance, and with the idea of beats as a quintessential music of deterritorialization, inspired by many places but not of any particular one. Beats as the musical outline of the modern globalization project.

Before the uniformity of streaming services, always-on social media and YouTube tutorials for everything, this is a portrait of independence and experimentation amid historical change. It’s a story of obsession, dedication and how the fringes brought about a musical revolution from inside bedrooms.

So this is what the book is about.

As for why it matters, there are various ways to look at it but the one I’ve repeatedly come back to is this idea of B-sides. In the figurative sense of the B-side as a foundation. The A-side is the story everyone knows — it’s hip-hop and dance music taking over the world, it’s your favourite producer, it’s your favourite pop song. And the B-side is the more niche story — the myriad subtleties that led to hip-hop and electronic dance music sounding the way they do today, your favourite’s producer favourite producer, the sample behind your favourite pop song.

Without these niche stories, the more popular story wouldn’t be complete, it wouldn’t even be possible. The people and music discussed in this book are part of these niche stories and the argument I’m making is that the beats of instrumental hip-hop and electronic music at the turn of the century, niche concerns with a small commercial footprint, played their part in shaping the sound of music today.

Here’s a concrete example. As I began writing this book the most popular song in the United States — the one about cowboys and living your best life — used a beat made by a Dutch teenager in his bedroom studio, sampling a random song from a popular 1990s industrial rock artist he’d never heard about, and sold online anonymously for $30.

In his excellent book about the birth and rise of disco, Love Saves The Day, Tim Lawrence nailed the status quo that followed the end of disco in the early 1980s and brought with it an explosion of electronic dance music: “The subsequent geographical spread of dance music across clubs, cities, nations, continents, and cyberspace, combined with the expansion of the genre into a myriad of self-generating sounds, means that only the most dexterous cartographer could hope to map its manic evolution.”

This book is an attempt at mapping part of this manic evolution – and the contagious spread of hip-hop which counterbalanced dance music’s rise – through the lenses of beat culture, B-sides, and bedroom producers/production. We’re going to cover a lot of ground, a lot of people, a lot of places. It’s a ride. It is not intended as an introductory text, that is I’m not here to convince you that beats are worthy of being considered music or tell you how it all started in the Bronx or Chicago or Detroit or London or Miami, and so on.

There were, of course, things that happened before this story begins, and which we might touch on briefly, and there are things that will continue to happen after it has been published. This book is not meant to be exhaustive or complete, rather it’s a reflection of my own personal journey and interests. As such there are likely going to be people and music that you, the reader, feel might deserve more attention.

In a lot of cases, others have already covered them better than I could — in books, documentaries, long-form pieces — and I invite you to use the book’s notes to find out more. One assumption is that you, the reader, have your own journey through beats and that, perhaps, this journey has brought you to this book. You may already know the foundations of what I’m talking about and you may already have your own understanding of where the story starts, who its people are, and what they did.

After all, it is 2020 and hip-hop and electronic music have been all around us for 40 years now. They’re pop music, let’s not kid ourselves. All this said, if you’re coming to this with little or no knowledge I hope it will spark your curiosity and I invite you to find out more by yourself. Music history can be a wonderful thing. Perhaps then you can think of this book as a time capsule, a collection of thoughts, ideas, and stories about some specific people, places, and music that you don’t have to wait centuries to unearth.

Bedroom Beats & B-Sides is dedicated to the memory of Gregory “Ras G” Shorter Jr. who I was lucky to know and call a friend. He was one of the best among us and taken too soon. airhorn

Bedroom Beats & B-sides is published on 6 November 2020 but you can pre-order it now and receive it in October.