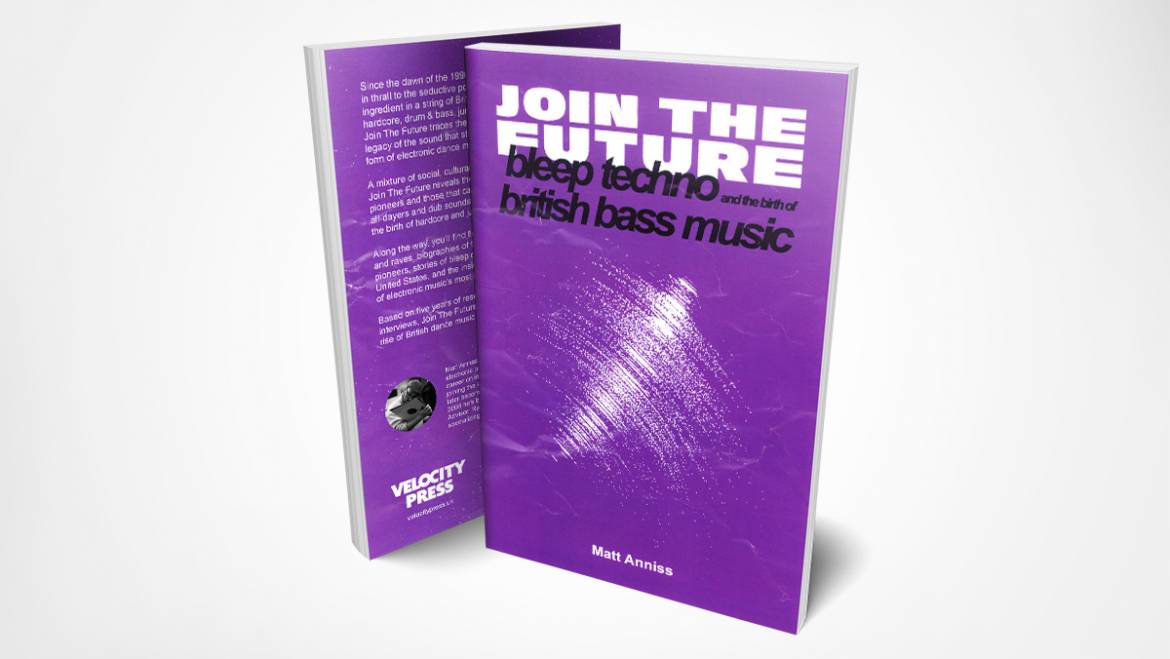

Join The Future by Matt Anniss is our first book, due out in December 2019. Here the author explains how it has been almost ten years in the making…

I’d like to tell you that the story of Join The Future began with an epiphany or at least some kind of profound revelation. In fact, it started with an argument in a club way back in the autumn of 2010.

I was deep in discussion with a group of young DJs about the roots of “bass music” – a collective term for that cluster of interconnected sub-genres of sub-bass heavy dance music – and offered the opinion that most of the music they played could be traced back to a short-lived style variously referred to as “Yorkshire Bleep”, “Bleep Techno” and “Bleep and Bass”.

They had never heard of “Bleep”, so I briefly explained what it was: a sparse, weighty style of heavy club music that drew influences from Detroit techno, Chicago house, electro and “steppas” style dub reggae. It was pioneered by bedroom producers and DJs in Bradford, Leeds and Sheffield, inspired the launch of Warp Records (a label that turns 30 this summer, fact fans) and should be considered the first distinctly British form of dance music.

They still looked unconvinced so I offered to prove my point by delivering a DJ mix for their Internet radio station (the now long departed Hivemind.fm) that joined the dots between original bleep classics and contemporary club cuts. I did just that, providing a 500-word justification for my supposedly contentious view of bleep’s significance to run alongside it. (Sadly, neither mix nor article is still online, but this more recent bleep and bass mix by yours truly should give you an idea.)

Four years and untold club conversations along the same lines followed before I decided it might be time to look deeper into the bleeps in a professional capacity. To scratch the itch further, I tracked down some of the sound’s better-known pioneers – or at least the ones who were willing to talk to me – and asked current DJs to talk about the sound’s significance to them.

The result was a chunky 2014 piece for Resident Advisor and a headful of ideas. I knew that there was a seriously good story here waiting to be told, ideally via a book, a compilation album or both. A few calls were made to contacts in the music industry, but the idea was eventually put on hold as life took over.

That the idea was eventually resurrected is down to three young graphic designers from Leeds. In January 2016, they sent me an email headed “Bleep book”. At the time, Kieran Walsh, Harry O’Brien and Jake Simmonds were final year students at Leeds College of Art.

They were all interested in bleep, had read my Resident Advisor article and wanted to create a book about it as their final assessed project. Somewhat cheekily, they wondered whether I’d be prepared to write said book, which they’d design and publish as a run of one book (yes, a single copy).

Most journalists would have told them to sling their hook, but I saw it as an opportunity to kick-start a project that had increasingly been infiltrating my thoughts. I agreed to work with them and provide a short book’s worth of copy with one caveat: once we’d got their show book out of the way we’d work together to publish an expanded, fully realized edition – either via a publisher or, at a push, ourselves.

The kick up the backside provided by an insanely short deadline – I had just over three months to research and write the book – helped sharpen my focus. Somehow I hit that deadline and in June 2016 found myself staring at our one-off book, now titled ‘Join The Future’ in tribute to the Tuff Little Unit record of the same name, in an art gallery.

It was a great moment but I knew it was just the start: if I was going to tell the story of bleep and bass and its role in kick-starting British dance music’s sub-bass revolution, then I’d need to interview a lot more people and do significantly more research.

Over the last three years, I’ve done just that. It’s been exhausting but also hugely rewarding. There’s been a lot of travel up and down the country to meet forgotten producers and overlooked pioneers, multiple trips to the British Library to check out contemporaneous media coverage, and untold hours spent conducting and transcribing phone interviews. I’ve been able to locate people whose remarkable stories had previously never been told (see my piece on original LFO member Martin Williams AKA DJ Martin for RBMA Daily), develop friendships with some of the key players and – most thrillingly for someone who is basically a hardcore music nerd – hear a clutch of unreleased tracks produced during the period.

Most importantly, I feel like I’ve scratched below the surface and dug deep enough to not only tell the story of bleep and bass, but a wider musical and cultural movement born not in London or Manchester – the two cities most discussed in UK dance music literature – but in basements, bedrooms and record shops in Yorkshire and the North Midlands.

For me, this feels important; not so much the book itself, but rather documenting a forgotten but essential and part of British dance music’s early evolution. There’s a very particular often-repeated narrative about the way the UK’s acid house revolution took place.

Most who were there will tell you that what we’ve been told is only a fraction of the story and based on half-truths and myths. I thought it was about time that some of those myths were challenged, as well as the idea that bleep was some kind of offshoot of hardcore (in fact, the earliest bleep records were made and released a year before their hardcore counterparts).

As a result, Join The Future is a radical rewriting of British dance music history that focuses not on what we’ve been told, but rather what we haven’t. I’m delighted that Colin Steven has snapped it up and will publish it as Velocity Press’s first title later in the year.

It’s a genuine labour of love that has consumed much of my working and personal life for the best part of five years. While Join The Future is primarily about the music and the people who made it, it’s also about communities, social change and post-industrial Britain at the tail end of the Thatcher era.

Above all, though, it’s the story of how British dance music fell in love with bass – a love that’s as strong in 2019 as it was in 1989.