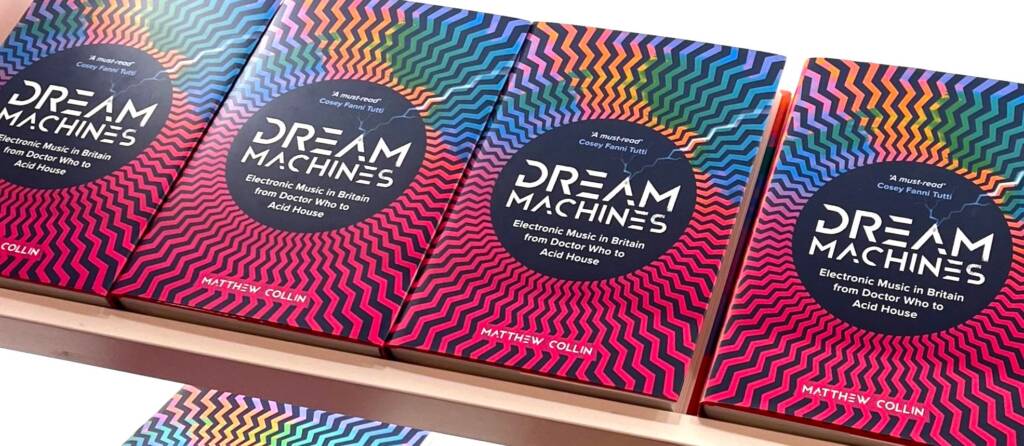

2024 continues to be a stacked year for fresh rave writing releases and new books about electronic music. But Matthew Collin’s new title Dream Machines is asking us to look beyond the familiar fever dream of UK electronic music since the acid house explosion and look deeper into the more obscure sphere of of earlier electronic music from the mid-20th century. Rob Smith chatted to Matt about what we can expect from his upcoming title.

You’ve written two previous titles about electronic music and club culture, why a third?

I suppose the reason is pretty basic really – I just adore electronic music! My first book Altered State was more of a ‘chemical generation’ story, all about ecstasy and the high, wild early years of the MDMA-fuelled rave scene in the UK, as well as the British authorities’ attempts to crack down on what they saw as a dangerous dance-drug culture corrupting the nation’s youth.

My more recent book Rave On was a journey through the globalised world of electronic dance music culture in the 21st century, from the US to Europe and beyond, examining how dance culture develops differently in the different places where it takes root, why the music means so much to the people who embrace it as the soundtrack to their lives, and what happened when corporate interests try to turn a participatory culture into a mass entertainment industry.

With Dream Machines, I set out to explore the formative decades of electronic music in the UK, when it still had this incredible power to amaze and sometimes even shock people. The book goes back to the music’s avant-garde origins just after World War II, then follows its development through the psychedelic sixties and the politically turbulent seventies and eighties into the synth-pop and electro era and then on into house and techno.

I wanted to take a more wide-ranging and inclusive view of electronic music’s evolution in Britain from 1945 to 1990, looking at the roles played by genres like dub, hip-hop, hi-NRG and psychedelic rock as well as the usual musique concrète innovators, synth-pop stars, ambient maestros and house music icons. I also tried to highlight the way the music’s development was shaped by scenes and cultural movements as much as advances in technology, from the LSD-inspired artistic explorations of the sixties to hippie festivals, sound system dances, hip-hop jams and acid house raves.

Meanwhile, all through the book I’m tracking how the UK’s electronic music culture was influenced by and reflected the huge changes within British society in the post-war decades, such as increasing multiculturalism and movements for civil rights and equality.

Moving further back down the electronic music timeline, how was the writing and interviewing process different? Were there still pioneers around to interview?

Two of the pioneers of UK electronic music, Delia Derbyshire and Daphne Oram, who both did groundbreaking work at the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, are unfortunately no longer with us. But many others are still around and still happy to tell fascinating tales of making electronic music and musique concrète when it was still considered incredibly strange. I talked to various originators from the Radiophonic Workshop who offered some wonderful insights into how music like the original ‘Doctor Who’ theme was painstakingly created with the most rudimentary equipment, years before synthesizers and samplers were on the market.

I was fortunate to be able to talk to loads of others who were originators in their genres – dub pioneers like Dennis Bovell and Mad Professor, electro-pop stars like Gary Numan, industrial avant-gardists like Throbbing Gristle veteran Cosey Fanni Tutti, as well as DJs and producers who created early UK house tracks.

Unfortunately, some of my interviewees passed away before the book was published, including the inimitable vocalist Mark Stewart, whom I had a hilariously surreal conversation with before his death. I regret that I didn’t get to talk to the mighty Jah Shaka before he died; his influence looms large over the chapter in the book about sound systems and dub.

What area of earlier electronic music history do you think is most overlooked?

I love the 1960s era of anarchic artistic experimentation when new sonic worlds were being explored and imaginative musicians like The Beatles were absorbing ideas from the ‘serious’ avant-garde and filtering them into pop. I also love stories about the 1950s reel-to-reel scene, when hobbyists were making DIY musique concrète in suburban living rooms and garden sheds and then playing their compositions to like-minded enthusiasts at tape-recorder clubs around the country. (You can read much more about this scene in the book Tape Leaders by Ian Helliwell.)

The do-it-yourself ethos is one of the themes that runs through Dream Machines, this very British make-do-and-mend attitude to creating electronic music – people using whatever equipment they can get their hands on to make the sounds they’ve imagined in their minds. It’s there at the beginning of the story in the post-World War II period when people were buying ex-military oscillators and other cast-off tech from army surplus stores to equip their home studios, and it goes right through to the acid house era of bedroom producers using cheap samplers and software.

Paul Hartnoll of Orbital tells a great story about how, when they made their rave classic ‘Chime’ at home, their biggest expense was the £3.50 that they had to spend on a high-quality cassette to master the track.

Who was the most obscure artist you rediscovered while writing the book?

A lot of the early stuff is relatively well-documented these days through the enterprising efforts of labels like Trunk Records that reissue obscure classics from the vaults. But there were some fascinating characters who were worthy of more consideration.

I loved the story of Desmond Leslie, an aristocratic UFO obsessive who was a distant cousin to Winston Churchill, owned a castle in Ireland and flew Spitfires as a fighter pilot for the RAF during World War II and then set up his own studio to make deeply strange musique concrète. The neighbours used to complain about all the weird noises so Leslie used to blame the racket on malfunctioning plumbing, his son told me. It’s a bit hard to comprehend now, but back then electronic music was seen by some people as freakish and disturbing.

I was also captivated by the recollections of Janet Beat, one of the UK’s first women electronic musicians in the 1950s, who told me how she had to combat the systemic misogyny of the times and the incomprehension of her own parents in order to follow her dream of becoming an electronic composer. When she was away at university, her father destroyed the reel-to-reel tapes of her early compositions, which he described as “Janet’s junk”, and she had to hide her ambitions from her music lecturers, who disapproved of electronic music. Other women musicians in the book also recalled facing similar problems – even in later decades, they were still being marginalised and undervalued.

Any favourite books, rave-related or in general?

It’s a bit of a golden era for electronic music and rave history books at the moment. I think it’s fantastic that there are now many more perspectives on this very diverse culture; more voices and more insights. There are really too many good books to list, but as this interview is on the Velocity Press site, I have to mention three great Velocity Press publications – Harry Harrison’s book on the DiY Sound System (Dreaming in Yellow), Mark Harrison’s chronicle of the adventures of Spiral Tribe (A Darker Electricity) and Matt Anniss’s bleep techno history (Join the Future).

In terms of brilliant writing about electronic music, Simon Reynolds is always thought-provoking and his new book Futuromania has to be a must-read, while two books by pioneering women DJs, Welcome to the Club by DJ Paulette and You Don’t Need a Dick to DJ by Smokin’ Jo, offer important new perspectives on UK club culture history.

Listening to any favourite radio shows or podcasts? Tunes-based or otherwise?

I’ve got a bimonthly Dream Machines show on Mutant Radio, an internet radio station founded by two brilliant young women in Tbilisi, Georgia, so I listen to a lot of their output, which ranges from left-field electronic dance music to avant-garde mixes by experimental artists. There’s a wonderful creative community around the station and I feel blessed to be a part of it.

It’s an exciting time for electronic music radio right now – there are great online stations all over the place, from the better-known dance music broadcasters like Rinse FM and The Lot to stations with amazingly diverse output like Noods in Bristol. I should also mention composer James Gardner’s radio series These Hopeful Machines, which brings the history of electronic music to life in a most eloquent and entertaining way and was an inspiration for me while I was writing my book.

Add Comment